Dunhuang Caves October 12 – 15

I had a rest day as my travel mates would be arriving from Hong Kong after 10:30 pm. For the first time since leaving Hong Kong on September 12, I could lie in bed till 9:30 am. What a luxury!

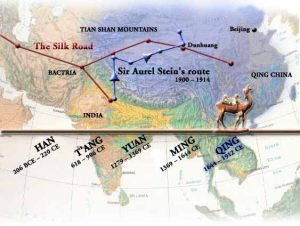

Situated in an oasis, Dunhuang敦煌 (formerly known as Shazhou沙州) had been inhabited as early as 2,000 BC. In 121 BC, it came under Chinese rule during the Han Dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD) when Xiongu who occupied this area was defeated by Han army in 121 BC.

Dunhuang had been a military town of importance owing to its strategic position at the crossroads of the ancient southern Silk Route and the main road leading from India via Lhasa to Mongolia and Southern Siberia, as well as controlling the entrance to the narrow Hexi Corridor 河西走廊which led to the ancient capitals of Chang’an (today’s Xian) and Luoyang, Dunhuang became a frontier garrison town along with Jiuquan, Zhangye and Wuwei. The Chinese built fortifications and sent settlers. It continued to prosper and became during the Tang Dynasty (618-907 AD) the main hub of commerce of the Silk Road, a major religious centre and cosmopolitan city.

Owing to its long history and social development and cultural exchange between China and the West, Dunhuang and the Mogao Caves in particular, are rich in historical and cultural treasures. The well-designed Dunhuang Museum with over 4,000 relics excavated from local areas is a must-see providing visitors a chance to better understand the history of China, its culture and the significance of the ancient Silk Road.

The museum has half a dozen exhibition halls. It is the first museum I have visited with good illustrations in four languages namely Chinese, English, Japanese and Korean. I spent a couple of hours and had a delightful educational tour.

There are numerous invaluable cultural relics excavated from tombs of past dynasties including Han (202 BC – 220 AD), Three Kingdoms (220-280), Jin Dynasty (265-420), Sui (581-618) and Tang (618-907). These relics include stone tablets, stone towers, pottery wares, lacquer beasts, kylin sculptures etc.

One of the halls exhibits documents, hand-copied books on ancient geography, military history and sutras written in the Tibetan language. In a special room, paintings and calligraphy work of well-known artists through the ages are displayed.

There is a rich collection of artefacts from the ancient Silk Road including silk, jade, pearls brocade, grains, pottery, tiles, ancient iron and bronze tools and weapons. It also explains the efficient communication and military systems developed since the Han Dynasty. There is a model of the Great Wall of the Han Dynasty and a torch from one of its beacon towers.

After spending a morning in the museum, I retreated to my room in the afternoon working on my travel notes on Pakistan. At 10 pm, Bian picked me up to go to the airport to greet my friends (Joy and Sunny, Flora, Kai, WH and Miranda). I intended to give them a surprise welcome. Unfortunately, they were early and were already at the arrival hall at 10:30 pm. Tonight, I was reunited with Flora, my roommate in Pakistan and Tajikistan.

Part 2 Dunhuang to Zhangye, Gansu

October 13 Saturday: Mogao Caves, Dunhaung

Mogao Caves 莫高窟

Also known as the Thousand Buddha Caves, the Mogao Caves contain some of the finest examples of Buddhist art spanning from the 4th to 14th centuries. The first caves were dug out in 366 AD by a Buddhist monk Le Zun who was later joined by another monk Faliang. By the time of the Northern Liang, a small community of monks had formed at the site. Cave-temple construction continued in Northern Wei, Northern Zhou, Sui and Tang Dynasties.

By the Sui and Tang Dynasties, the caves had become a place of worship and pilgrimage for the public. The number of caves reached over a thousand. Caves constructed by monks to serve as shrines with funds from donors were elaborately painted. The paintings and architecture were serving as aids to meditation, as visual representations of the quest for enlightenment, as teaching tools to inform the illiterate about Buddhist beliefs and stories. The major caves were sponsored by patrons including Chinese emperors, ruling elite and important clergy. Other caves were funded by merchants, military officers etc.

After the Tang Dynasty, the site went into a gradual decline. Construction of new caves ceased entirely after the Yuan Dynasty. The importance of the Silk Road decline after the much of Central Asia was converted to Islam. Trading via sea-routes began to dominate Chinese trade with the outside world. The Silk Road was officially abandoned during the Ming Dynasty. Most of the caves were abandoned though the site remained a place of pilgrimage and worship by the local people.

During late 19th and early 20th centuries, western explorers began to show interest in the ancient Silk Road and the lost cities in Central Asia. Some who passed by Dunhuang noticed the murals, sculptures and artifacts. The biggest discovery was however made by a Chinese Taoist named Wang Yuanlu who appointed himself guardian of some of these temples. On June 22, 1900, he discovered a walled-up area behind one side of a corridor leading to a main cave (Cave 16). Behind the wall was a small cave storing an enormous hoard of manuscripts (Cave 17). This library cave containing some 50,000 manuscripts had been walled up in the 11th century. Wang took some manuscripts to show to various officials who showed varying level of interest. He re-sealed the cave following an order by the governor of Gansu in 1904.

Wang had let Aurel Stein and Paul Pelliot acquire a significant number of manuscripts and items at a fee in 1907 and 1908 respectively. A Chinese scholar Luo Zhenyu who edited some of the manuscripts Pelliot acquired into a volume which was published in 1909 as “Manuscripts of the Dunhuang Caves”. Luo and others persuaded the Ministry of Education to recover the rest of the manuscripts to be sent to Beijing. Later, expedition by the Japanese in 1911, the Russian in 1914 and the American in 1924 took some items while some caves were damaged and vandalised. Contents of the library have been dispersed around the world and the largest collections are now found in Beijing, London, Paris and Berlin. Today, the International Dunhuang Project attempts to coordinate and collect scholarly work on Dunhuang manuscripts and other material.

Chinese scholars and painters including Zhang Daqian began to appreciate the significance of the caves. In 1944, the Research Institute of Dunhuang Art (which later became the Dunhuang Academy) was set up to look after the site and its contents. Mogao Caves was inscribed on the World Heritage List in 1987. From 1988 to 1995, a further 248 caves were discovered to the north of the 487 caves already known since the early 1900s.

The art of Dunhuang covers more than ten major genres such as architecture, stucco sculpture, wall paintings, silk paintings, calligraphy, woodblock printing, embroidery, literature, music and dance, and popular entertainment. It is impossible to detail the caves in a few paragraphs. Information of some of the caves are available at www.e-dunhuang.com.

I find the following features worth mentioning.

First, the caves are examples of rock-cut architecture. But the local rock is a soft gravel conglomerate that is not suitable for either sculpture or elaborate architectural details.

Second, of the 735 caves currently exist in Mogao, the best-known ones are the 487 caves located in the southern section of the cliff. The 248 caves found to the north were living quarters, meditation chambers and burial sites for the monks. The caves at the southern section are decorated while those at the northern section are mostly plain.

The caves are clustered together according to their era, with new caves from a new dynasty being constructed in different part of the cliff. The dates of around 500 caves have been determined.

- Sixteen kingdoms (366-439) – 7 caves the oldest dated to Northern Liang period

- North Wei (439-534) – 10 caves

- Western Wei (535-556)- 10 caves

- Northern Zhou (557-580) – 15 caves

- Sui Dynasty (581-618) -70 caves

- Early Tang (618-704) – 44 caves

- High Tang (705-781) -80 caves

- Middle Tang (781 – 848) – 44 caves (During this period, Dunhuang was under Tibetan occupation)

- Late Tang (848-907) – 60 caves

- Five Dynasties (907-960) – 32 caves

- Song Dynasty (960-1036) – 43 caves

- Western Xia (1036-1227) – 82 caves

- Yuan Dynasty (1227-1368) – 10 caves

Third, the murals are extensive covering an area of 45,000m2. The most fully painted caves have paintings over the walls. Ceilings are also painted with geometrical or plant decoration and Flying apsaras (angels) or celestial beings. The apsaras totalling over 4,500 (the largest one at 2 metre and the smallest one at 3cm) are vivid and beautiful.

The murals are valued for the scale and richness of content as well as their artistry. Early murals showed a strong Indian and Central Asian influence in the painting techniques used, the composition and style of the paintings as well as costumes worn by the figures. A distinct Dunhuang style began to emerge during Northern Wei Dynasty with more Chinese elements. The artistry of the murals reached its apogee during the Tang Dynasty.

The art reflects the changes in religious belief and ritual at the pilgrim site. Jataka tales (previous lives of the historical Buddha) are often depicted in early caves. Paradise paintings of various Buddha covered the walls of many caves during the Tang Dynasty when Pure Land Buddhism was popular.

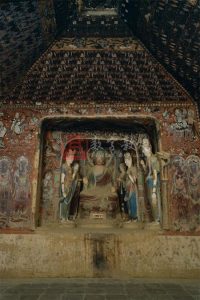

Fourth, there are more than 2,000 surviving sculptures which were first constructed on a wooden frame, padded with reed, then modelled in clay stucco and finished with paint. The Buddha is generally shown as the central statue, often attended by bodhisattvas, heavenly kings, devas, and apsaras, along with yaksas and other mythical creatures. Most of the statutes were made with clay. But the giant ones had a stone core. The sculptures are brightly painted.

Fifth, with a normal ticket (¥100 in low season and ¥200 in high season) a visitor can watch a digital film in the visitor centre before taking a 75-minute guided tour to eight to 12 caves. No photo is allowed inside the caves.

About 60 caves are open to visitors with a normal ticket. But special arrangements are required for caves 45, 57, 156, 158, 217, 220, 254, 275, 321 and 322 at additional fee.

We have made special arrangements through the Dunhuang Academy to visit five special caves (¥200 per cave per person).

Cave 321 (Early Tang) with a truncated pyramid ceiling featuring a large medallion surrounded by the draperies of twisted vines and half medallions that extend to the four slopes covered with the thousand Buddha motifs. The Central Buddha is the original Tang work. The other statues were all renovated or repainted in the Qing Dynasty. The south and north wall was completely occupied by illustration of the Ten Wheel Sutra and the Amitabha Sutra (about the belief of Ksitigabha) respectively. Construction was mainly sponsored by the Zhang, Lihu and Cao families.

Cave 45 (High Tang) is one of the outstanding caves containing the most well-preserved Buddha statute group (a seated Buddha, two disciples (Anada & Kasyapa), two bodhisattvas with feminised appearance and two heavenly kings). Outside the niche are images of Avalokitesvara and Ksitigarbha (the only great Bodhisattva appearing in monk form). The south wall contains the Avalokitesvara sutra illustration. The illustration on non-Han merchants encountering bandits is fine and most lively. On the north wall is a depiction of the Pure Land (i.e. the paradise) with Amitayus at the centre with explanation on ways to reach paradise on the vertical margins at both side of the mural.

Cave 57 (Early Tang) of medium size with a truncated pyramidal ceiling with two coiled dragons and lotuses with draperies extending to the four slopes. Walls of this cave were covered with thousand Buddha motifs with a group of seven statues including a seated Buddha, two disciples and four bodhisattvas (one bodhisattva has been lost) in the niche. The murals show illustrations of Jataka (Conception and the Great Departure), a preaching scene, seven Buddhas, Medicine Buddha and Maitreya Sutra. This cave contains the famous and most beautiful bodhisattva with the smile of Mona Lisa.

Cave 220 (Early Tang) is one of the representative Tang Dynasty caves. It has a truncated pyramidal ceiling and a niche in the west wall. In 1944, the Dunhuang Art Research Institute removed the upper layer murals on the four walls thus discovering the original Early Tang paintings.

The west niche contains a central Buddha flanked by two disciples and two bodhisattvas. The walls contain illustrations of the Vimalakirti, Manjusri, Amitayus sutra and the Medicine Buddha. There are two scenes of whirling dance in the north wall. In 1975, the Institute after removing the surface layer of a painting discovered a new styled illustration of Manjusri dated 925 AD, seven donor figures, an inscription about the examination of the family tree written by Zhai Fenda. Each picture in this cave is a masterpiece and the image of Vimalakirti is of the highest level. The dancing scene and the music band in the Medicine Buddha illustration are precious material for studying the music and dance.

Cave 158 (Middle Tang) is a Nirvana Cave featuring a large reclining Buddha at a length of 15.8 metre. The ‘Mourning scene of the ten principal disciples’ on the south wall, the ‘Mourning princes from various kingdoms’ and ‘Lady Maya (mother of the Buddha) on hearing the new bad news’ on the north wall and images of bodhisattvas and arhats are remarkably lively with various facial expressions.

After having visited five special caves on the first day, we had an excellent guided tour with Wang the second day to see ten caves with a ¥200-ticket. It was Sunday and there was already a long queue at the entrance at 9am. As we had made prior arrangement, we could enter without problem.

After having visited five special caves on the first day, we had an excellent guided tour with Wang the second day to see ten caves with a ¥200-ticket. It was Sunday and there was already a long queue at the entrance at 9am. As we had made prior arrangement, we could enter without problem.

We spent almost four hours visiting two Sui caves (426 and 428), four Early Tang caves (96, 323, 328 and 329), two Late Tang caves 16 and 17 (the Library Cave), one Song cave 55 and one Five Dynasties cave 61 (the largest cave in Mogao Caves). As Wang was only available in the morning, we had to skip the digital film which was scheduled for our group at 9:45am.

We began our tour shortly after 9 am at Cave 16 & 17 where the story of Dunhuang caves began with the discovery of the wall-in library on June 22, 1900 by Wang Yuanlu. Cave 17 containing a statue of Monk Hong Bian, a Monastic Official in Heix Region, served as his memorial cave.

There is too much to see in each cave. I found it impossible to grasp the history and salient features of each cave in 15-30 minutes. Hence, I stayed close to Wang listening to her interpretations while keeping my eyes wide open and following her torch which lit up the exquisite and beautiful mural paintings.

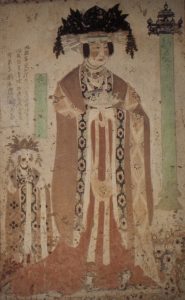

After a whirlwind tour, I find the mural paintings and sculpture even more awesome than after my first visit in 1991. The exquisite paintings of the female donors in Uighur costumes in Cave 61 of the Zou family (which is the biggest cave with an area of about 200m2), are well-preserved. I begin to appreciate the transformation of art from Indo-Greek to Chinese forms and expressions. I can tell the slim and elongated figures of the Sui Dynasty from the fuller body and flair of the Tang Dynasty. Even the apsaras reached perfection in their forms and movements during the Tang Dynasty.

We finished the tour at the iconic Cave 96 with a 35.5m-high Maitreya Buddha, the largest statute built in 695 AD under the edict from Empress Wu Zetian (the only female emperor in Chinese history). I had visited this cave in 1991 but somehow felt something was different. Wang explained the cave has been restored in recent years to its original form with the floor of the cave a few meters below the entrance. As a result, the Big Buddha looked even bigger and imposing as I was standing below the base of the seated Buddha.

We had two busy days in Dunhuang. In addition to having two guided tours to see 15 caves, I visited two museums next to the caves, had afternoon tea in the 5-star Dunhuang Hotel with full views of the Mingsha Mountain, climbed the sand dunes to watch sunset and saw two performances, a new show called “Encore Dunhuang” (¥688) in a brand new purpose-built hall and the dance and music “Silk Road show” (¥588) at the Dunhuang Grand Theatre.

We had two busy days in Dunhuang. In addition to having two guided tours to see 15 caves, I visited two museums next to the caves, had afternoon tea in the 5-star Dunhuang Hotel with full views of the Mingsha Mountain, climbed the sand dunes to watch sunset and saw two performances, a new show called “Encore Dunhuang” (¥688) in a brand new purpose-built hall and the dance and music “Silk Road show” (¥588) at the Dunhuang Grand Theatre.

I left Dunhuang with mixed feelings. During my first visit in September 1991, I spent two days at Mogao Caves and climbed Mingsha Mountain in peace. Today, Dunhuang is smart and prosperous with countless posh hotels. I find Mingsha Mountain Park another theme park with noisy crowds and an army of some 7,000 camels ferrying tourists to sand dunes. Ladder steps are installed to enable visitors to climb to the lower ridge of the sand dune next to the Crescent Spring. Though the city and things are tidy and well-organised, I yearn for the Dunhuang I visited in 1991.

I left Dunhuang with mixed feelings. During my first visit in September 1991, I spent two days at Mogao Caves and climbed Mingsha Mountain in peace. Today, Dunhuang is smart and prosperous with countless posh hotels. I find Mingsha Mountain Park another theme park with noisy crowds and an army of some 7,000 camels ferrying tourists to sand dunes. Ladder steps are installed to enable visitors to climb to the lower ridge of the sand dune next to the Crescent Spring. Though the city and things are tidy and well-organised, I yearn for the Dunhuang I visited in 1991.

The Mogao Caves have become a ‘Must-see’ for both Chinese and seasoned travellers. The Dunhuang Academy with over 1,500 staff is trying its best to preserve the invaluable treasure while satisfying the tourists’ demands. It is a difficult balancing act. The Academy has done a great job in managing the site and regulating the crowd. By digitalising the caves, people can have free virtual tours online. But to receive a maximum of 6,000 visitors a day is still a daunting task. Mural paintings are delicate. How long can this invaluable art treasure last at the onslaught of mass tourism?

We saw two cultural performances and paid for the best seats. But we were all disappointed. “Encore Dunhuang” first premiered on September 20, 2016, is an immersive 90-minute Chinese theatre piece which gives audience a chance to travel through time while they walk through four zones and experience key moments and characters in the 2,000-year history of the city. The Aqua Blue Theatre, a large glass structure that is said to look like a water droplet poised in the vast Gobi Desert, is modern and purpose-built for the performance. As my Putonghua is not too good, I cannot fully appreciate the play. The setting is grand with exuberant art work and modern design, most colourful and exquisite costumes, nice music and lighting. But it is too extravagant and pretentious to my humble taste.

The play “Silk Road” with singing and dance, first performed in 1979 is about friendship between Chinese people and a merchant from Central Asia. It has received high acclaim. But I find the music, dance and acoustics all stay at the 1980-90 level. If you have seen world-class performances, you can give it a miss.

October 15 Monday: Dunhuang – Yulin – Jiayuguan 325km

Dunhuang Caves is used as a collective term to include Buddhist caves sites in and around the Dunhuang area including Mogao Caves, Western Thousand Buddha Caves, Eastern Thousand Buddha Caves, Yulin Caves, and Five Temple Caves.

Today, we began our journey along the Hexi Corridor with a stop at the Yulin Caves some 100km east of Dunhuang. We set off around 8 am and drove along G30 before turning off to take G314. We saw some most beautiful elm trees covered with golden leaves along the Yulin River.

Yulin Caves 榆林窟 (though not a World Heritage Property) with 42 cave-temples dugged on both side of the river, are a hidden gem. They house some 250 polychrome statues and 5,000 m2 of wall painting dating from the Northern Wei to Yuan Dynasty. Only the caves on eastern cliff are open.

We arrived at 11 am and spent three hours at the site. I paid ¥20 for a general ticket and our young enthusiastic guide showed us Caves 6 (Tang), 9 & 11 (Qing). In addition, we paid ¥550 each for visiting four special caves 2 & 3 (Western Xia), 4 (Yuan) and 25 (mid-Tang).

We arrived at 11 am and spent three hours at the site. I paid ¥20 for a general ticket and our young enthusiastic guide showed us Caves 6 (Tang), 9 & 11 (Qing). In addition, we paid ¥550 each for visiting four special caves 2 & 3 (Western Xia), 4 (Yuan) and 25 (mid-Tang).

The most interest thing about the Yulin caves is that they contain works belonging to the Western Xia Dynasty (1038-1227 AD) which ruled the area of present-day Gansu Province and Ningxia. As in Mogao Caves, the paintings mainly feature buddhas, bodhisattvas, apsaras and jataka tales with some secular scenes depicting donors, representatives of ethnic minorities, marriage ceremony, musicians and dancers, and daily activities such as farming, wine-making etc.

Caves 2 and 3 belong to the Western Xia / Tangut period thus providing invaluable insights into the art and culture of these nomad people. Cave 2 contains one of the most beautiful images of “Water -Moon” Avalokitesvara.

Cave 3 with the diversified contents and art of both exotic and esoteric Buddhism, supported respectively by Chinese and the Tibetans, is a most representative cave with the most matured and unique art. The cave is rectangular in plan with a dome ceiling. In the central back is an octangular altar with three steps on which stand a few statues of the Qing Dynasty. In addition, there are statues of 18 arhats standing on a platform built at the lower parts of the four walls. The ceiling is covered with a Mandala: in the centre are five Buddhas of five directions. The walls depict Buddha’s life stories, a mandala of 51 headed thousand-armed and thousand-eyed Avalokitesvara of exotic Buddhism, illustration of the Amitayus sutra, the Pure Land, Vimalakirti sutra and Manjusri and Samantabhadra, many mandalas and the donor figures.

Cave 25 is considered the most magnificent of the Yulin caves. Constructed during the period when the area was under Tibetan occupation, it is a strictly Tibetan Buddhist cave, with unique murals and other art works in a clearly identifiable “Tibetan style”. The main chamber is a square in plan with a central altar and the front chamber is rectangular in plan. Both are connected by a long corridor. The original paintings are well preserved and outstanding examples of fine painting of the era. On the east wall is a Mandala of Eight Bodhisattvas, an Amitayus sutra illustration on the south wall and a Maitreya sutra illustration with single images of Avalokitesvara, Mahasthamaprapdta and Kistigabha bodhisattvas on the north wall. On the two sides of the entrance in the west wall are illustrations of Manjusri and Samantabhadra.

We left around 2 pm. Bing who had just finished her Dunhuang pilgrimage tour with the Buddhist Charity Organisation at Yulin, continued her travel with us while other returned to Hong Kong the following day. We had a long drive to Jiayuguan 嘉峪關and did not reach our hotel till 7 pm.