Mardin, Diyarbakir & Mount Nemrut

Day 7 Tuesday: Tatvan – Hasankeyf – Midyat – Mardin 320km

We were now entering the hot region in East Anatolia. We first stop at the Malabadi Bridge, an Ottoman bridge near the city of Batman which has sprung up in recent years on discovery of oil in the area.

Today we had our first full view of the Tigris River at Hasankeyf which has many caves and the ruins of a medieval Byzantine city. But this city will soon be submerged under water on completion of the controversial Ilisu Dam.

The Turkish government has launched an ambitious South-eastern Anatolia Project (SAP) which involves the construction of 22 dams in the region, to generate power, control flood and store water for irrigation. One of the planned dams is to be built on the Tigris near the village of Ilisu and along the border of Mardin and Sirnak Provinces. This dam would flood the majority of the ancient city of Hasankeyf which history stretches back over 10,000 years, displace physically and economically some 60,000 people living in 199 villages and hamlets which will be fully or partially affected by the flooding.

Construction work which began in 2006, was delayed and only completed last year. The work has been disrupted when international funding was withdrawn owing to its disastrous impacts on Hasankeyf and by the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) militants. As it would affect Iraq’s water share of the Tigris which might lead to the drainage of the Mesopotamian marshes and destruction of its ecology system, Iraq has also protested and asked the Turkish authorities to postpone filling of the proposed Ilisu reservoir.

On the way to Hasankeyf, we first stopped at a royal tomb that has been relocated to this higher ground.

Then we drove a short distance to reach the Tigris. We had full views of an old Ottoman bridge which would be submerged soon.

The whole area is now a construction site. We could see a few structures (fortress and palace) located at hill tops in the distance.

We walked up a hillside to look at some abandoned cave dwellings. From here I had a commanding view of the Tigris and the whole area. I could see two long new bridges, tunnels, a network of highways and new settlements in a distance.

When will this area be flooded with its ancient history buried under the water? A sad story for humanity and civilisation!

It was very hot. We soon moved on and arrived at Midyat for lunch. Midyat is an ancient city that can be traced back to the Hurrians during the 3rd millennium. Many different empires that had ruled over it include the Mitannians, Assyrians, Armenians, Medes, Persians, Greeks, Romans, Byzantines, Abbasids, Seljuks and Ottomans.

Midyat is an historic centre of the Syriacs/Assyrians, an ancient people who trace their origin to Akkadian Empire established in Mesopotamia around 2200 BC. Syriac is a Semitic language directly related to Aramaic, the native tongue of Jesus Christ. Syriac Orthodoxy was established after the first division in Christianity in 431.

The Syriac population which constituted the majority of the city’s population as late as the Assyrian genocide in 1915. From a 1975 population of 50,000 (10% of Mardin Province’s population, only 2,000 were left in 1999 at the end of the conflicts between the Kurds and Syriacs. Today, about 500 Syriac Christians live in the city and five Syriac churches are still standing.

After lunch, Kylie and I strolled around the silver bazaar which must have been a Christian quarter. The buildings around the bazaar are mostly built with stones. Many houses look big but empty. I was surprised to find many wine shops.

After a short drive, we arrived in Mardin around 4pm and checked in the Gazi Kongi Hotel. I fall in love with Mardin on first sight.

Mardin rising steeply over a flat plain and standing at 1083m above sea level, looks majestic and overpowering from a distance. Owing to its strategic location on a rocky hill near the Tigris and overlooking the plain, it served as the capital of Turkic Artuqid dynasty between 12th and 15th centuries. Today, it is the capital of Mardin Province and has been considered as an open-air museum, thanks to the Artuqid architecture of its old city. Mardin was effectively closed to tourism throughout the 1990s owing to the on-going Turkey-PKK conflict in the surrounding countryside.

The small old town is atmospheric littered with beautiful buildings, monuments and vistas. There are 22 mosques, three madrasahs and nine churches. Most buildings use the beige coloured limestone rock. At the hill top is a fortress (which is not accessible to the public).

The small old town is atmospheric littered with beautiful buildings, monuments and vistas. There are 22 mosques, three madrasahs and nine churches. Most buildings use the beige coloured limestone rock. At the hill top is a fortress (which is not accessible to the public).

We like our boutique hotel which has been nicely converted from an old house. We had a large and comfortable room with a balcony. It was so hot that we did not go out till 6pm.

There is only one main street that traverses the town from one end to another through its centre. Apart from the main street that is open to one-way traffic, other streets are narrow and winding and only accessible on foot.

We followed Sabahattin to visit the Great Mosque (Ulu Camii) which was constructed in the 12th century by the ruler of the Artukid Turks, Qutb ad-din Ilghazi. It has a ribbed dome and a minaret soaring above the city. Its interior is simple and empty. Unlike other mosques I have visited, it is very cozy with many kids playing the “hide and seek” game.

Next, Sabahattin took us to shop selling hand-made soap in the bazaar. We must have spent over half an hour in learning about the secrets of half a dozen of organic soap made from olive, garlic, coconut, pomegranate etc.

Next, Sabahattin took us to shop selling hand-made soap in the bazaar. We must have spent over half an hour in learning about the secrets of half a dozen of organic soap made from olive, garlic, coconut, pomegranate etc.

I bought six pieces (10TL each). Later we found out similar products selling in other shops on the main street cost much less. A kilo of soap might be selling for 20-30 TL. Is the soap we bought superior in quality or have we overpaid? Anyway, I shall find out when I use it later.

I bought six pieces (10TL each). Later we found out similar products selling in other shops on the main street cost much less. A kilo of soap might be selling for 20-30 TL. Is the soap we bought superior in quality or have we overpaid? Anyway, I shall find out when I use it later.

The region is known for nuts and pistachio coffee. We went to a big shop right at the entrance of the main street of the old town and sampled half a dozen of nuts. The pistachio coffee is so good that we bought a few as souvenirs.

We went to an eatery near the hotel after 8pm. As we were not hungry, we only had chicken wings and a skewer for dinner. I had a wonderful sleep.

Day 8 Wednesday: Mardin – Diyarbakir 110km

After a nice breakfast, we drove to the Deir-Al-Zafaran (The Monastery of St. Ananias) located about four kilometres from the old city. The monastery founded in 493 AD, is one of the oldest monasteries in the world and the largest in Southern Turkey.

The site has been the centre of religious worship for centuries while the monastery itself is built over an ancient temple, possibly built in 1000BC and dedicated to sun worship which provides the foundations to the main part of the monastery building. The roof of the temple to the sun is essentially a flat arch. From 1160 until 1932, it was the seat of the Syriac Orthodox Patriarch until the Patriarchate was relocated to Damascus.

The complex is impressive and open to pilgrims and tourists. The monastery has 365 rooms in total. But the residential and the most sacred sections are closed to all except monks.

Our second stop was the Kasimiye Madrasah which construction was completed under Sultan Kasim of the Akkoyunlu dynasty and opened in 1469.

The main two-storeyed building is rectangular with an ornamental portal from the south. The most interesting feature is the water channel and pool in the middle of the courtyard which symbolises the four stages of manhood. The water source is a funnel in the wall that represents birth. The water from the pool drains through a narrow slit that represent death and sirat (a narrow bridge on hell which leads to paradise).

On our way to Diyarbakir, we stopped at the Ten-Eyed Bridge over the Tigris. I could see the city walls of Diyarbakir on the horizon.

Before checking in the Radisson Blu Hotel, we went to a nice local restaurant for lunch. The speciality here is lamb liver which is nice but high in cholesterol. I had chicken but got a small piece from Sabahattin. I find the liver soft and tasty.

Diyarbakir

Situated on the banks of the Tigris River, the old city is surrounded by an almost intact and dramatic set of high walls of black basalt. First built by the Roman Emperor Constantius II in 349 and extended by Valentinian I between 367 and 375, the fortified city has been an important centre and regional capital during the Hellenistic, Roman, Sassanid and Byzantine periods, through the Islamic and Ottoman periods to the present.

Owing to its historical significance and outstanding cultural value, the Diyarbakir Fortress together with Hevsel Gardens Cultural Landscape located on an escarpment in the Upper Tigris River Basin have been listed on the World Heritage List. This property includes the city walls of 5800m – with its 82 watch towers, four gates, buttresses and 63 inscriptions from different historical periods and the 700 hectares fertile Hevsel Gardens that link the city with the river and supplied it with food and water.

Diyarbakir is the capital of the Diyarbakir Province and often considered the unofficial capital of the Northern Kurdistan. It has been a focal point of the conflict between the Turkish state and various Kurdish insurgent groups. Medieval mosques and madrasahs dot the old city. Unfortunately, large parts of the historical district of Sur were destroyed in fighting between the Turkish military and the PKK between November 8, 2015 and May 15, 2016.

Diyarbakir is the capital of the Diyarbakir Province and often considered the unofficial capital of the Northern Kurdistan. It has been a focal point of the conflict between the Turkish state and various Kurdish insurgent groups. Medieval mosques and madrasahs dot the old city. Unfortunately, large parts of the historical district of Sur were destroyed in fighting between the Turkish military and the PKK between November 8, 2015 and May 15, 2016.

The temperature soared over 35°C. We decided to take refuge in the Archaeological Museum. The entrance fee is only 6TL and most value-for-vale. It has excellent display and illustrations with artifacts from the Neolithic period, through to the Early Bronze Age, Assyrian, Urartu, Roman, Byzantine, Artuqids, Seljuk Turk, Aq Qoyunlu, and Ottoman Empire periods.

I am impressed by the presentation and illustrations of major archaeological sites in the region. I did not realise that the oldest site at Kortik dated back to about 10,000BC. I have learnt more about the region’s rich history.

I am surprised to find an enormous Armenian church next to the Archaeological Museum. The restored Mother Mary Church is awesome. Somehow, I feel uneasy: something horrible must have taken place here. I shall find out later.

I also dropped in the Atatürk Museum – a moderate house where Atatürk stayed and worked during his visit to the city.

As there was too much to see, we asked Sabahattin to meet us at 7pm instead of 6pm. Kylie was tired and we had a drink in the Hasan Pasa Hani, a popular spot for shopping and a drink.

Then we walked across the main street to reach the Great Mosque, the former St. Thomas Christian Church which is one of the oldest churches in history. The mosque which is famous for hosting four different Islamic traditions and can accommodate up to 5,000 worshippers, is considered by some to be the fifth holiest site in Islam.

This mosque is the oldest and one of the most significant mosques in Mesopotamia. Following the capture of the city by Muslims in 639, a mosque was built but ruined later. The existing St. Thomas Church was converted into a mosque and had been used by both Muslims and Christians. In 1091, Sultan Malik Shah directed the local Seljuk governor to rebuild a mosque on the site. Completed in 1092, it is similar to and heavily influenced by the Umayyad Great Mosque in Damascus.

The mosque complex built with alternating bands of black basalt and white limestone is majestic with some interesting features.

- A complex of buildings are built around a courtyard 63m long by 30m wide.

- The façade of the courtyard is highly decorated with two-storey colonnade on the east, south and west sides but only one storey on the north side.

- The western façade rebuilt between 1117 and 1125 reuses columns and sculptural mouldings from a Roman theatre.

- An Ottoman sadirvan (ablution fountain) and a platform for praying are located at the centre of the courtyard.

- The mosque has a prayer hall which makes up the entire south wall of the courtyard. The portal of the mosque is carved with two lions attacking two bulls.

- There are lavish carvings and decoration of the columns of the courtyard.

- Many Kufic inscriptions record in details the rebuilding and additions made to the complex throughout its long history.

We next visited the small Sheikh Matar Mosque situated in the Yenikapi Street at the city’s walled historical district of Sur. The mosque is best known for its unique minaret based on four columns, dubbed the Four-legged Minaret.

From here, I could see the cross of St Giragos Armenian Church, one of the largest and most important Armenian churches in the Middle East, and Keldani Church behind high enclosures. They are closed to visitors.

We were back on the main street and passed by a 16th century hani which has been converted into a hotel. The traditional building with bands of black basalt and white limestones is impressive. Sadly, the renovation work, interior decoration and hotel facilities are not up to standard.

We were back on the main street and passed by a 16th century hani which has been converted into a hotel. The traditional building with bands of black basalt and white limestones is impressive. Sadly, the renovation work, interior decoration and hotel facilities are not up to standard.

The sun was setting. The city wall is not high but part of the staircase looks unstable. I am not afraid of height but owing to my knee problem, I am weary of falling.

Standing high up on the wall, I could see the lush green Hevsel Gardens, the Tigris and the Ten-Eyed Bridge at the far end. The sunset was not impressive.

We were back in the hotel shortly after 8 pm. Though Kylie and I were not hungry, we popped in the restaurant in Radisson Blu to see what was on offer. The restaurant was totally empty. A sociable and enthusiastic manager explained it was normally the case on Friday evening. We decided to sit down to have a light supper.

The staff were wonderful and friendly and we were treated like VIPs. At the end, Kylie had soup, I had a glass of local white wine and we shared a big grilled seabass. The staff treated us with freshly baked bread and a few starters. All the kitchen staff came out for photos with us. I suddenly became a star!

We only paid 110TL for a delicious dinner and a most enjoyable evening. I finished my great day with a dip in the pool and a few minutes’ stay in the hamam.

Day 9 Thursday: Diyarbakir – Mount Nemrut – Adiyaman 320km

One should not leave the city without a proper look on the city wall and a visit to the 1700-year-old Syriac Church of Virgin Mary.

Sabahattin drove us back to the old city. We spent half an hour walking along the top of a section of the city wall. Parts of it are in poor conditions. I wonder how long the wall can last if it is not properly maintained.

Sabahattin drove us back to the old city. We spent half an hour walking along the top of a section of the city wall. Parts of it are in poor conditions. I wonder how long the wall can last if it is not properly maintained.

After a short ride, we arrived in the Lalabey neighbourhood which looks relatively poor with unpaved paths. We found the church and were met by Fr. Yusuf Akbulut, the priest of the church who gave us a guided tour.

First constructed as a pagan temple in the 1st century BCE, the current building dates back to the 3rd century and has been restored many times. The church holds holy relics with a piece of the cross and the bones of the apostle Thomas. There is a small chapel dedicated to St Jacob. It is a treasure worth visiting.

The church is still in use as a place of worship. But the number of Syriac Christians has dropped to about 50.

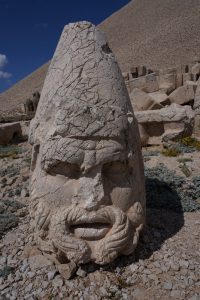

At 11 am, we left Diyarbakir and had a scenic ride to Mount Nemrut, a World Heritage Site known for its colossal statues erected around a royal tomb from the Commagene Kingdom at the summit of a 2,134-metre-high mountain.

After the fall of the Seleucid Empire in 190 BC, many new kingdoms emerged. Commagene, one of the Seleucid successors occupied the land between the Taurus mountains and the Euphrates. The territory of Commagene corresponds roughly to the modern Turkish provinces of Adiyaman and northern Antep. The kingdom began in 163 BC and ended when it was annexed by the Roman emperor Vespasian in 72 AD.

Antiochus I Theos (c 86 BC – 38 BC) who was half Armenian and half Greek, was the most famous Commagene king who ruled from 70 to 38 BC. He established a dynastic religious programme which included the Armenian, Greek and Persian deities as well as himself and his family. He supported the cult as propagator of happiness and salvation.

His tomb was the most important area to the cult: the complex was constructed in a way that religious festivities could take place. He allocated funds for these events from properties legally bound to the site. He also appointed families of priests and hierodules to conduct the rituals, and their descendants were intended to continue the ritual service in perpetuity. He wanted his people to enjoy the festivities.

Antiochus’ tomb was forgotten for centuries till Karl Sester, a German engineer arrived in 1881 while assessing transport routes for the Ottomans. Archaeologists began excavation in 1883. Then came Theresa Goell who made her first visit in 1947 and dedicated her life to this site. Though subsequent excavations have failed to reveal the tomb of Antiochus, it is still believed this is the site of his burial.

We got off at the carpark and took a shuttle bus to the base of the tumulus measuring 49-metre tall and 152 metre in diameter.

We walked uphill following a well-designed path to the Western Terrace. It is an awesome sight: I can image how the five gigantic statues of Apollo, Hercules, Antiochus, Zeus and Tyche were seated facing the expansive land below. The heads of the statues have been removed deliberately at some stage from their bodies and are scattering throughout the site. The statues appear to have Greek-style facial features but Armenian clothing and hair-styling.

The western terrace contains a large slab with a lion showing an arrangement of stars and the planets Jupiter, Mercury and Mars. The composition was taken to be a chart of the sky on July 7, 62 BCE. This might indicate the beginning of the construction of the monument. There are also two lions and two eagles on the ground.

The site has preserved stone slabs with bas-relief figures that are thought to have formed a large frieze. These slabs display the ancestors of Antiochus who included Armenians, Greeks and Persians.

We followed the path to the Eastern Terrace which is well-preserved. The layout is the same as those in the Western Terrace except the statues are even larger. They also scatter on the ground. There are clear descriptions on each statue and the layout. I think the site should best be visited at sunrise or sunset. By the time we left the site, it was well after 4 pm.

We had a brief stop at the Cendere Bridge erected by the XVI Legion in the honour of Roman Emperor Septimus Severus.

Weather changed suddenly. We had lightning and thunder when we drove off to our next destination. But soon, we had sunshine again. The countryside with extensive farm land was impressive.

Our final stop was the Karakus Tumulus, a funerary monument built in 30-20 BCE near the modern village of Cukurtas. Karakus means “black bird” and the monument is so named because there is a column topped by an eagle.

The tumulus is surrounded by groups of three Doric columns each about 9m high. The columns are topped with steles, reliefs and statues of a bull, lion and eagle. An inscription indicates that presence of a royal tomb that houses Queen Isias and Princess Antiochis and Aka I of Commagene.

The sky suddenly darkened with ghastly gale wind sweeping across the tumulus. We quickened our pace to complete our walk round the base of the tumulus. I hurried back to the vehicle and drove off.

We were back on the road heading to Adiyaman which is still 50km away. The landscape with rolling hills and colourful patches of cultivated wheat fields after harvest against a dark sky looked wild and dramatic.

We stayed at the new Hilton Garden Inn and met Sabahattin’s second elder brother who was taking an English couple from Gaziantep to Van. We went out together and I had delicious chicken and lamb kebab for dinner. I felt tired after a long day.